The Electoral College — How it Works, Why it’s Broken, and How to Fix it

Ever since I started paying attention to US elections in the nineties, I’ve been aware that the Electoral College system in the US seems odd. It’s hard to explain, which indicates it might be over-complicated, and possibly broken.

But as a non-American, I’ve never quite understood what’s wrong with it in detail. So I went and did some reading, and this is my understanding of how the Electoral College works, why it’s broken, and how it needs to change.

Because I’m explaining this to myself, and because I’m a five-year-old, I’ll explain it as simply as possible. I’ve included sources at the end.

Note: I’m not American, no, but I’m heavily invested in America, have family there, have most of my customers there, and have worked most of my life in the US. That’s why American politics affects me individually, and why I try to understand it, even though I can’t vote.

How the Electoral College System Works

In one sentence: The Electoral College is a big group of people who formally vote to decide who becomes the President of the United States, based on how people in each state voted in the election.

In the US presidential elections, people directly vote for a presidential candidate… kinda. At the core of it, they put a name down on a ballot card — just one name (oh OK, also another name for Vice President).

But it’s not the “popular vote” that carries the election.

Instead, votes are counted according to a system of “electors” who represent the population of the US vaguely proportionally.

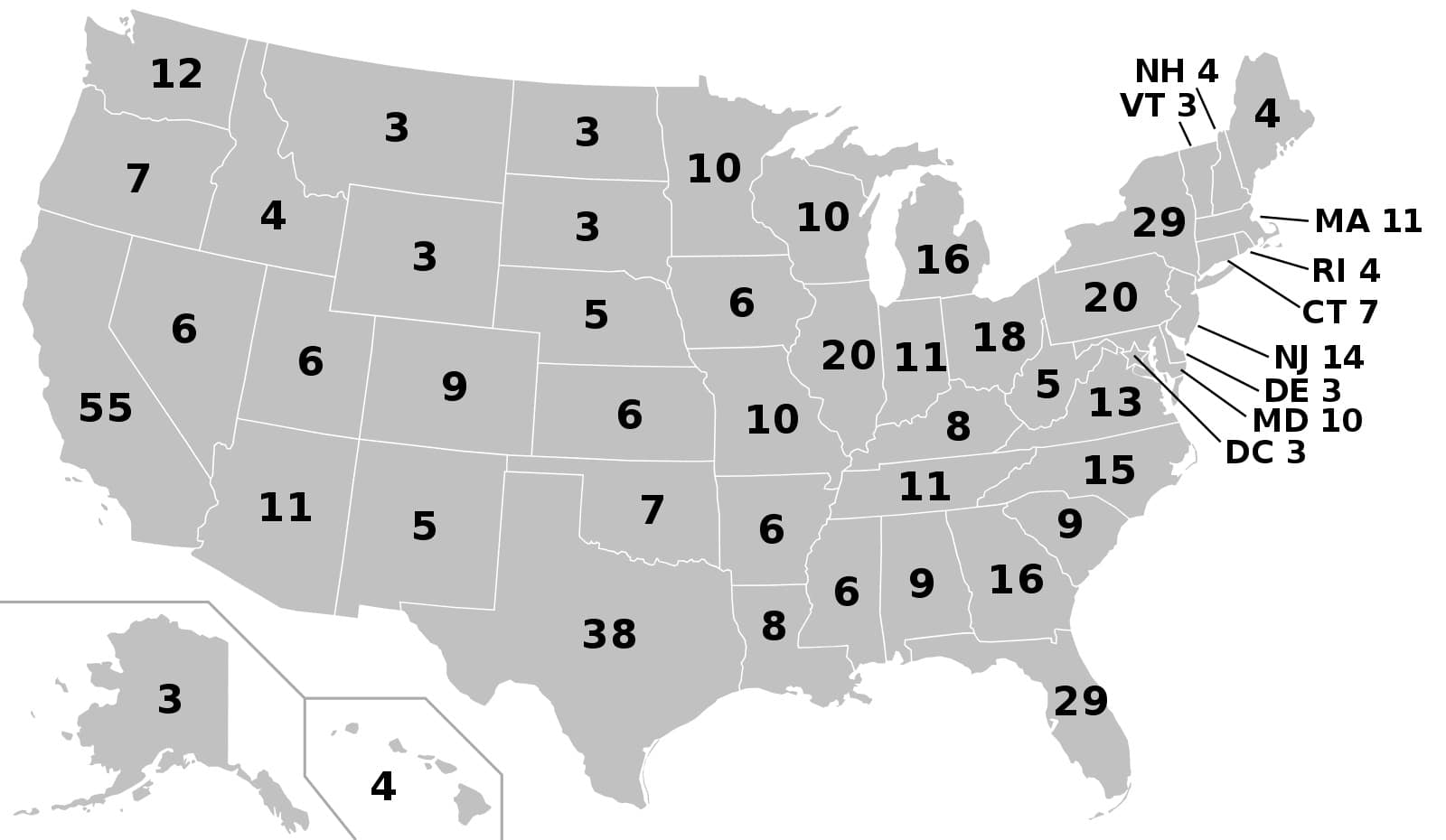

Every state gets a certain number of electors. They get

- Two electors, representing the two members of the Senate, plus

- One elector per member of the House of Representatives (the number of which is decided by the census, described below).

That adds up to 538 electors in the US in total (hence fivethirtyeight.com, a politics site that used to be kind of a big deal):

- 100 electors for the Senators

- 3 electors for the District of Columbia

- 435 electors for all the Representatives

The number 435 remains constant but gets redistributed every 10 years according to the national census which re-counts the population and re-apportions Representatives at the same time.

Who are the electors? The electors aren’t the same people as the Representatives and the Senators. They’re independent, semi-random people. The party nominates its own people to be electors. Usually, they’re long-standing party activists, officeholders, or donors. They’re just individuals, and usually, they’re not elected.

So how do the electors vote? They vote for whoever wins the most votes in the state (in nearly all states).

In the election, each state counts all its ballots. Whoever the majority go to, the electors all have to vote for (with a couple of exceptions below), otherwise they’re castigated as “faithless electors”, which to me sounds like the title of a boring movie. (Ten faithless electors attempted to not vote for Trump in 2016, and seven succeeded.)

So, for example, if in Texas 50% of the voters vote for the Republican candidate, and 49% for the Democrat candidate ( 1% undecided), as is forecast in 2020, then all of Texas’ 38 electoral college votes have to go for the most popular candidate in the state — even though that doesn’t represent the will of around half the voters. This is called “winner takes all”.

(To be fair, all elections are “winner takes all”, overall.)

A couple of exceptions to the above state-based “winner takes all” system are Maine and Nebraska. In Maine and Nebraska, they have a “district” system. In those, two electors (the ones representing the senators), vote for the most popular candidate overall, and one elector represents each congressional district’s popular vote. Colorado tried to implement something similar in 2004, but voters rejected it.

The candidate who wins 270 votes by the electoral college — the number 270 being one more than half of 538 colleges (half of 538 is 269) — wins the presidential election.

Why the Electoral College was formed

It’s important to understand why the Electoral College even exists. Why did the Framers of the Constitution and those who made the amendments build the Electoral College at all? Was a popular vote even an option? C’mon wasn’t it kind of obvious?

Yes, a popular vote was an option… but they ditched it. The Electoral College was created by the framers of the U.S. Constitution as an alternative to electing the president by popular vote or by Congress. Because they decided those weren’t a good idea for various reasons.

The Framers of the US Constitution actually had a hard time figuring out how to vote for the President (and later, the Vice President, when that became a thing). Some said that Congress should pick the president. Some said the Senate should, giving large and small states an equal say. Some said popular vote. The Electoral College system was an elaborate compromise between all of these.

At the time, no other country in the world democratically elected their chief executive, so the US was in uncharted territory. (This was surprising to me. Didn’t the Greeks invent democracy ages ago? Hah! Typical Greeks*, inventing stuff then dropping the ball.) And people distrusted executive power, just as they do today. After gaining independence from the British the Americans didn’t want some despot to take the place of the King.

Here’s what people’s objections to the various proposals were:

- Election by Congress or the Senate: Too much opportunity for corruption. Good call, in my opinion.

- Election by popular vote: People thought that 18th-century voters were ill-informed and uneducated (they were, relatively), especially in rural outposts. Rude! Secondly, they feared a headstrong “democratic mob” steering the country astray, which happens all the time anyway. And third, a populist president appealing directly to the people could command dangerous amounts of power (this has happened nearly every time). (See this article for more details on this.) Finally, popular vote would disenfranchise slave owners, and poor slave owners felt sad about this.

(* I’m Persian. I make superficial fun of the Greeks because it’s part of a 2000-year tradition, but recognise that we’re basically the same, tea-drinking, baklava-eating people, and even look pretty much the same.)

“Slave owners”?? A quick word on slavery and the “three-fifths compromise”

It took a few reads for me to understand this, but slavery had a big role in the establishment of the Electoral College. It’s not the thing that damns it in itself, but if this was how the sausage was made, it makes you call the whole sausage into question.

Describing the Electoral College system is often put as describing “big states vs small states”. But back in the time of the framing of the Constitution, it was about “North vs South”, and in that sense about populations, and slaves.

In a direct election system, the South would have lost every time, as a large chunk of their population was slaves — who couldn’t vote.

But an Electoral College allowed states to count slaves, albeit at a discount — each slave counting as three-fifths of one person, in a weird compromise — I don’t even want to joke about those conversations. That compromise is what gave the South the advantage in presidential elections. In fact, eight of the first nine presidential races were won by a Virginian — Virginia was the most populous state at the time and had a massive slave population.

America has abolished slavery, but the electoral college system that was designed to not disadvantage the South (and thus advantage it) is now entrenched in the Constitution and pretty hard to change.

So, given nobody wanted the above options, the compromise was that they’d appoint temporary “electors” to implement the will of each state.

Alexander Hamilton and the other Framers (naively, I think) believed that the electors would be able to ensure that only a qualified person becomes President. Nobody could manipulate electors, because they met only once and thus couldn’t have other vested interests, or be manipulated by foreign governments. They were like ninjas, appearing in the night, casting their ballot, and leaving. They were exactly like ninjas.

The Constitution doesn’t say how a state’s electors have to vote. The idea was that the electors would be “enlightened individuals” who’d vote according to their individual discretion. But that’s not how it panned out.

But as of today, 33 states have passed laws requiring electors to vote as directed (this includes Maine and Nebraska, who don’t have “winner takes all”). In the other states, electors vote as pledged out of tradition, other than in the rare case of “faithless electors“.

The Framers even assumed that no single candidate would often win a majority of electoral votes, and so the decision would go to the House of Representatives. (This has only happened twice; the last time being in 1824.)

But they didn’t foresee the rise of political parties, which meant that people would support one party or another, and always see a candidate get the required number of votes to win the presidency.

Why the electoral college system is broken

There are several reasons the electoral college system is broken. (There are a few reasons it’s good — see those below.)

The problems in a nutshell can be summarised as being that the electoral college system is undemocratic. Defenders of the electoral colleges say that it’s no more undemocratic than the Senate or the Supreme Court.

Problem 1: The Electoral College often doesn’t represent the will of most Americans.

Firstly, the Electoral College often doesn’t represent the will of the majority of Americans.

In the 2000 elections, which many remember, Al gore won 0.51% more of all votes cast for the presidential election — but lost the electoral college vote to George Bush.

This wasn’t the first time that this happened. In fact, there have been five elections in which the person who won the electoral college would have lost by the popular vote.

Some of them were very contentious. In 1824, Andrew Jackson won 10.5% more popular votes than the winner, John Quincy Adams. And in 1876, Samuel J Tilden won 3% more of the popular vote than President Rutherford B. Hayes. Both of these are larger than Hillary Clinton’s still significant margin of 2.1% of the popular vote.

In every case where an elected President won the electoral college but didn’t win the popular vote, it was a Republican president (though it should be noted that over that time period, the definition of “Republican” has evolved dramatically since Abraham Lincoln’s time).

Problem 2: The “winner takes all” system means a few states decide the President for many

Secondly, the electoral college system doesn’t effectively convey the will of a state.

The “winner takes all” system that nearly all states employ means if most people in a state vote one way — even if the margin is very small — then all the electoral college votes go towards that candidate.

The “winner takes all” system has some weird consequences:

- In states that are decidedly blue or red, the candidates do very little campaigning. Nothing’s going to change California from being a blue state — the margin is a massive 2:1.

- In states that are very blue or red, people think there’s not even any point voting. Californians and New Yorkers really feel like there’s no point; it’s going to be blue, anyway.

- Conversely, candidates do a disproportionate amount of campaigning in swing states, and voters know it’s up to them.

“Winner takes all” is why Florida, always a battleground, gets a lot of attention. They have a huge number of votes — 29 electors in the 2020 election, based on the 2010 census. And to win Florida, it means candidates have to do a lot of pandering to elderly voters, Cuban Americans, orange farmers, and any other groups that represent some group of Floridians.

In the 2016 election, Clinton and Trump (and their teams) made a total of 399 campaign appearances after officially winning their party’s nomination. Of these appearances, 375 were in just twelve states: Florida, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia, and Michigan, and six smaller states. In other words, they campaigned almost exclusively in only twelve states.

Problem 3: Electoral College votes don’t represent the majority of voters in a state

Under the electoral college system, the candidate who gets all the electoral votes in the state — e.g. all of Florida’s 29 votes out of the total of 538 — only has to have the most votes compared to anyone else. This is the “plurality” system.

That means that if a candidate wins 47.5% of the vote in a state, and the next top candidate gets 47.3% of the vote, then the candidate with the 47.5% gets all the electoral votes in the state even though it’s not the will of the majority.

If those numbers sound weirdly familiar, it’s because it’s the result of the 2016 presidential election in Michigan, and you’re probably a savant (or highly obsessive) for remembering them. I had to Google them!

In 2016, Donald Trump won all the electoral college votes, totalling 101, in six states where he received less than 50 per cent of the popular vote: Arizona, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. I’d credit him with being a political genius, but even he was surprised.

Problem 4: Electoral colleges favour the smaller states

Fourthly, the electoral college system disadvantages the most populous states and largest cities. (This is also cited as an advantage.)

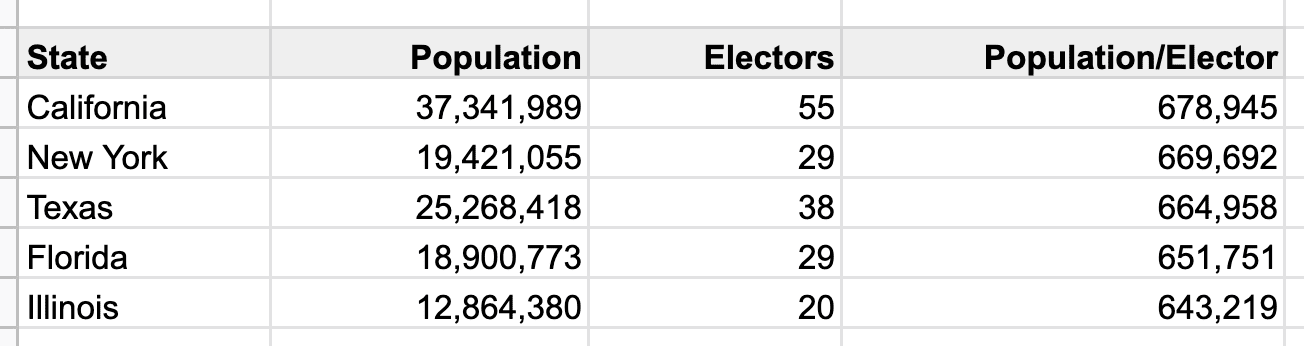

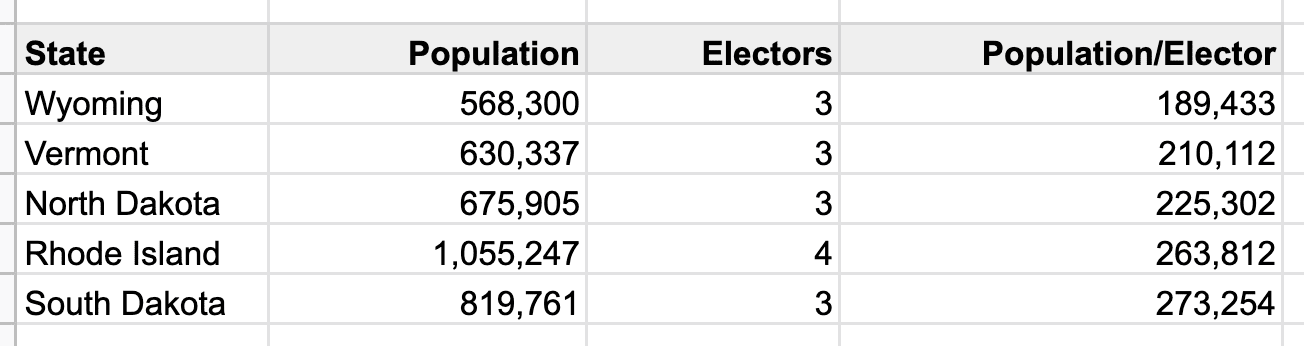

According to the 2010 US Census apportionment of the members of the House of Representatives per population, the top five districts in population/elector are California, New York, Texas, Florida, and Illinois.

You might notice these are pretty huge states. And Illinois. Well, it’s not small. But anyway, in some of the BIGGEST states, people’s votes count for the least!

And the bottom five districts in population/elector are Wyoming (the state with the smallest population in the US), Vermont, North Dakota, Rhode Island, and South Dakota.

Check my work in the Google Sheet, if you want. (Trigger warning: Array formulas, and also it vaguely looks like work.)

This means that in five of the smallest states, a person’s vote for the President is weighted about three times as much as a person’s vote in the largest states. I can’t bold-face this enough.

Smaller states are also favoured because they always get two votes for their two senators. (It’s a whole other question about how small states get such disproportionate power in the Senate, but I think this was the general idea of the Constitution.)

This distortion means that even if “winner takes all” is eliminated, voters in smaller states would still have a disproportionate influence.

It’s akin to saying “Everyone in your house has a vote. But two people live in the master bedroom, so let’s give them 0.7 of a vote each. And our surly teenager who lives in the in-law unit in the yard gets three votes.” It’s exactly like this.

Problem No. 5: An independent candidate can distort the election, and even hold it hostage

Finally, under the current system, it’s very hard for third parties to win elections. People consider voting for an independent to be a wasted vote.

But an independent candidate can significantly — and deliberately — change the outcome of the election.

In 2000, Ralph Nader (running as a nominee for the Green Party) won 1.6% of the vote in Florida, probably shifting the state from Al Gore to George Bush. George Bush won Florida (and thus the election) after a Supreme Court intervention, an intense recount, and 537 votes out of six million cast. FIVE HUNDRED AND THIRTY SEVEN VOTES! I once did more push-ups than that in an hour. If Ralph Nader hadn’t run, those voters would probably have voted Democrat.

In 1968, George Wallace — who ran on a pro-segregation ticket that would have anyone who’s not a neo-Nazi hanging their heads in shame — wasn’t even trying to win the presidential election. He was being an usurper, which I call a bloody troublemaker. His whole strategy was to prevent either major party from winning a majority in the Electoral College. This would throw the election into the House of Representatives, where Wallace thought he had enough bargaining power to strongly influence who the winner would be.

Part of this problem comes from the fact that in the US elections, people put one name down and not a list of preferences. So you vote for one candidate with no fallback if your “dreamer” candidate doesn’t make it. Thus, if independents are running, they can distort the election.

Of course, independents often can have power in other systems, too. In multi-party countries like my home country of Australia, and also in our arch-rivals New Zealand, governments are often formed by “coalitions” that don’t have enough representatives to form government by themselves. But the whole system is geared towards the fair election of independents (e.g. with tickets with multiple candidates), unlike in the US.

Some Defences of the Electoral College system

There are a few benefits to the electoral college system that are worth mentioning.

The Electoral College’s first advantage (which is also a disadvantage) is that it favours smaller states. While this distorts the election on a per-head basis, it does give those small states a voice and means they can’t be steamrolled by the voices in the large states who like big-state things like Teslas and taxes and free stuff, which nobody else likes.

If we relied on just the popular vote, then the candidates would just campaign in the biggest centres — Los Angeles, New York, and a few other big cities and densely populated regions. Country towns and rural areas would get looked over.

People who like the electoral college system say that this imbalance is by design. It’s just like the imbalance of the Senate — every state gets two votes, irrespective of size. This is the “federalist” view — that the will of the country has to reflect the will of the people as well as the will of the fifty independent states. You know what Federalist means because you read the Federalist papers, right? Or you watched Hamilton… with subtitles.

The second advantage of the Electoral College system is that the Electoral College avoids situations where a person who doesn’t win the popular vote also doesn’t win the election.

This is related to — but different from — the situation where the loser of the popular vote wins the electoral college (e.g. Trump in 2016).

The most recent example is Bill Clinton, who won 301 of the electoral college votes in 1992, but only won 43% of the popular vote. His opponent, George H. W. Bush (“Bush Senior”), only won 37.5% of the popular vote. By the popular vote, neither would have won.

How to fix the Electoral College system — some ideas

Here are the main ways in which people are talking about reforming the electoral college system.

Approach 1: Move to a popular vote

The main way in which people want to change the Electoral College system is by moving to the popular vote.

To change the Electoral College you need to change the US Constitution. This means a two-thirds majority in the House and Senate, or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of state legislatures.

That’s not easy. In fact, with America as divided as it is, it’s quite hard to see it happening again. The last amendment was in 1992.

But do you really need a constitutional amendment? There is one alternative way of moving to the popular vote without an amendment — states can agree on how to assign their electoral college votes. For example, all the states can agree to assign their electoral college votes in accordance with the national popular vote.

There is a national effort called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (or “the Compact”) underway to move to the popular vote in this way, without requiring a constitutional amendment. It needs approval by states representing 270 of the electoral college votes. In 2024, the compact is now at 17 states + DC, totalling 209 electoral votes, and thus only needs 61 more votes to go into effect. (See the status here.)

When I first wrote this article in 2016, the Compact was at 11 states + DC and 172 electoral votes. So there has been notable progress. The Compact believes the US may get to a popular vote by 2028.

The states who object to the Compact do so either because they’re smaller states (who wouldn’t get as much influence under a popular vote) or are states who typically vote Republican, who would also not benefit under a popular vote (unless they changed strategy, which I’m sure they’d do). But it should be noted that the Compact has bipartisan support, even if it’s uneven.

There is also the question of whether the Compact would even be constitutional, seeing how it’s designed to undermine the constitution. It would be reasonable to expect litigation against it to reach the Supreme Court, which now has a conservative majority.

Approach 2. Move to a popular vote and implement rank-based voting.

One problem with the simple move to a popular vote is that it doesn’t address the problem of third-party candidates.

People can vote for whomever they choose. But a third-party candidate can prevent any candidate from getting more than 50% of overall votes, or a plurality. In the 57 presidential elections since 1789, no candidate received fifty percent of the vote on 18 occasions.

A move to a popular vote under the current system by agreement between the states would elect as president the winner of the plurality of the vote. But this means that in many situations — particularly if more candidates show up — a candidate for whom the majority of people never explicitly voted could become president.

To address the problem, the voting system would need to be changed to a system of rank-based voting, similar to that used in Australia.

This is how rank-based voting would work:

- If one candidate has an outright majority of first-place votes, that candidate wins.

- But if no candidate has a majority in the first round, second-choice preferences come into play.

- The candidate with the fewest number of first-choice votes is ruled out, and voters who had ranked that candidate first have their votes transferred to the candidate they ranked second.

- This continues until a single candidate gathers a majority, with subsequent preferences transferring as candidates get eliminated from the bottom up.

Sounds good, but implementing rank-based voting would require a constitutional amendment, so… sad face.

Approach 3: Eliminate “winner takes all”

Eliminating “winner takes all” is another shortcut to a kind of popular vote. It would mean that a state’s electoral votes would represent the votes of its electors.

States can appoint their electoral votes however they want, so this is totally constitutional.

Eliminating “winner takes all” would force candidates to campaign even more broadly, because they couldn’t count on winning all a states votes.

Maine and Nebraska don’t employ a winner-takes-all all system. In those states, two electoral votes go towards the plurality vote winner, and the rest of the votes are by constituency.

Eliminating “winner takes all” retains the problem (or benefit) of disproportionate representation of smaller states.

Approach 4: Implement rank-based voting at a local level

Finally, there is some discussion around implementing rank-based voting on a state level, particularly in pivotal states like Arizona, Florida, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

States can do this, because how they conduct elections and how they assign their electoral college votes is up to them — constitutionally. Or at least, it’s not unconstitutional, so it flies.

If you implement rank-base voting in just the pivotal states, then those states’ votes are more representative of the people’s choices. Third-party candidates won’t be able to distort the outcome of an election as they did in 2000 in Florida. People would say “I want this crazy guy, but then this other guy if my crazy guy doesn’t make it”. So votes for the crazy guy + the other guy would outnumber the third person, who let’s call George W Bush.

If a few states implement rank-based voting, it won’t solve all the problems of the electoral college system. Candidates would still visit small states and swing states.

Final thoughts

It took a while to write this, but I learned a lot in the process.

If you find anything that’s wrong up there (or just based on overly biased information), feel free to tell me. This is all from my own reading and listening to podcasts and I’m sure there are gaps.

There is obviously bias in the content, because how could there not be? The sources are biased and I’m a fleshy watery organic object with inevitable bias. However, I did read some sources from supporters of the college system.

If you find it overly objectionable, I’d like to know why.

Sources

I’ve linked sources in-line as much as possible. But here are the major ones I used in my haphazard Googling.

- History House Archives — Electoral College Fast Facts

- Wikipedia — List of all US presidential elections in which the winner lost the popular vote

- US Census — 2010 Census Apportionment Data

- Texas Monthly — Texas Is Screwed More by the Electoral College Than Any Other State, Despite Our Size

- ABC Australia — From Lincoln to Trump: The long evolution of the Republican party

- Harvard Law Review — The Danger of the National Popular Vote Compact

- Politico — Is the Electoral College Doomed?

- History.com — Why was the Electoral College Created?