How Inflation Works and Why Control it — Explained Simply

Recently I heard someone claim that inflation was caused by the central bank printing money.

This is a common political trope. The general theory is that inflation is a tax that we didn’t vote for and unjustly enriches a small minority.

Any theory like this that attempts to explain complicated things with a strong spin raises my alarm bells, so I decided to figure out what it meant, and to then write this very simple explanation (an ELI5) of how inflation works in modern economies, and how central banks try to reign it in and prevent deflation.

Whenever inflation spikes, or interest rates are raised, people have the same questions, including

- Why does inflation happen?

- Why (or when) is inflation good or bad?

- What do interest rates do?

- What is “quantitative easing”?

Here’s my attempt at explaining these things simply — starting with inflation.

What Causes Inflation — People Wanting More stuff (or money)

In a normal, balanced market (that’s not run by dictators and that’s not in the throes of revolution), inflation is caused by people wanting more stuff for their money, or spending money and not caring about what things cost.

For example

- “Hey, people seem to like this stuff I sell. I need more money. Maybe I can charge more for my stuff” –> prices go higher because someone raised them.

- “I found oil in my backyard, jackpot! Now I’m rich! I’m going to go buy a bunch of stuff and I don’t even care what they cost” –> prices go higher because this person isn’t bargaining as much.

- “Where’s the toilet paper? I’d pay anything for a roll!” –> Prices go higher because someone is desperate for a life necessity (though I’d argue to just learn to use a bidet, French-style.)

So basically prices gently go up in a normal market as people either want more money, or want more stuff. Economists call this demand pull but I’m trying to avoid unnecessary terms.

The reason this is a “normal” market is that because equilibrium actually means gentle growth. It’s OK to want more stuff. We always want stuff, it’s a natural human function.

- We’re worried about our kids, so we want to have a nest egg for the future.

- We are hungry now, so we want food.

- We want the world to be a better place.

Wanting means demand, and demand leads supply, so causes inflation.

You can see how natural inflation is in the team-building exercise “Helium Stick”.

In Helium Stick, a team of people is given a stick (like a broomstick or PVC pipe). Each person’s hands must always be touching the stick, supporting it on everyone’s hands. The challenge is to lower the stick to the ground.

The problem is, even keeping the stick at one steady height is very difficult. As everyone tries to keep touching the stick, they all exert slight pressure on it as they try to keep up. The stick starts rising. Soon the stick is magically over their heads and nobody has any idea how it gets there.

Inflation works the same way. Prices start going up, so everyone else starts increasing prices to keep up.

What “Good” Inflation Is

A steady economy is one that gradually rises. This means that inflation has to exist but it can’t be too high and it can’t be too low.

In other words, for the world to remain at equilibrium, we have to grow very slightly. This means we’re all functioning normally as humans and wanting stuff, but are remaining sane about it.

There are a few reasons inflation is good, in general. The main two of these are that

- When people expect prices to increase over time, they’re more likely to be incentivised to spend now, rather than later. This keeps people consuming, which means they have to make more money. To make more money they have to try new things to make more money, which means education, research, innovation and entrepreneurship.

- Low inflation means an absence of deflation, which means a shrinking economy and less things for people. People are not incentivised to do anything and society stops progressing.

It sounds a bit convoluted, but that’s as simple as I can get it.

But how much is “good” inflation?

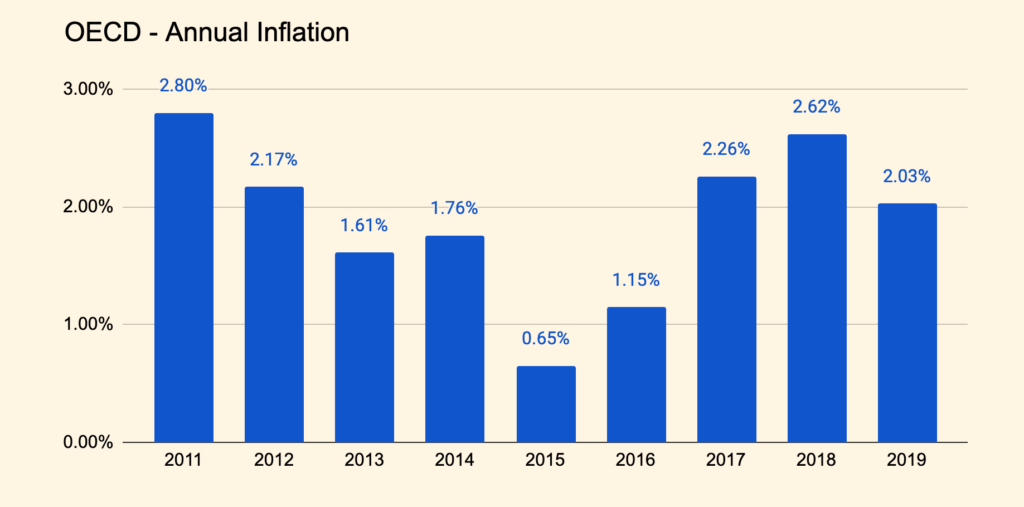

Generally, central banks target inflation of 2-3%. More than that is bad, and less than that is also bad.

For example

- Australia targets 2-3% and this has been its policy since the 1990s

- The European Central Bank targets at or below 2%

- The US Federal Reserve targets 2%

They usually hit these targets, too… roughly. Here’s how well Europe (the OECD, or Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) has done with inflation targets over the last 10 years:

How Deflation Happens (and Why Deflation is Bad)

There’s also the concept of deflation. This sounds great to a lot of people. Prices getting lower? Sign me up!

The problem is that since a steady economy means slow growth. So what happens in a deflating economy? Stagnation, bank raids, and hoarding.

In a society where nobody is buying anything, people also stop producing for other people. This means, in a nutshell, that unless you’re producing it for yourself, you won’t get electricity, water, or food.

The main way deflation happens is when people are too scared to spend money and nobody has money to buy things. This happens during depressions.

The consequence of that is that businesses make less money, causing lay-offs and people to have less money to consume food.

The worst-case of deflation is a spiral downwards as companies and people hoard cash and goods and the economy grinds to a standstill.

So, governments and central banks try to avoid deflation.

How central banks use interest rates to prevent excessive inflation and avoid deflation

So we know too much inflation is bad and too little is also bad.

How can we manipulate inflation? Well in many ways, but the way reserve banks do it now is by controlling interest rates.

- When interest rates are high, people borrow less and they also save more (to earn that sweet interest), so they spend less, and this reduces inflation.

- When interest rates are low, people can borrow more and they’re less incentivised to save, so they spend more, and this increases inflation

The central bank sets the rate at which commercial banks can borrow from the government.

For example, if the central bank sets interest rates at 1%, that’s what Citi borrows money at.

Then, after borrowing money from the government at 1%, Citi either pays you 0.9% interest on your savings account, or lets you borrow money at 1.1%. They keep the difference.

There are two other tools used to affect inflation as well. These are:

1. Change cash supply by increasing or decreasing reserve requirements

Banks are supposed to keep a certain amount of the money on hand. If you’ve stored $100 with them, they don’t have it locked away in a box — they only keep a tiny fraction of it (usually around 10%). The rest of it they lend to people or invest.

Reserve banks rarely use this tool — it’s more a once in a decade (or so) tool. After the 2008-09 financial crisis, many central banks increased reserve requirements.

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, the US Fed reduced reserve requirements to 0%. So they don’t have to have any of the money that you have stored with them.

2. Change cash supply by buying and selling Government Bonds

You might read in the news about open market operations. That’s what these are.

When the central bank buys bonds from banks, the banks have more cash to loan.

Conversely, when the central bank wants to reduce cash in the system, it sells cheap bonds to big banks at prices they don’t want to pass up on.

Wait, what about Quantitative Easing?

After the 2007-08 financial crisis, all the major reserve banks of the world – the US Fed, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan — all launched quantitative easing (QE) programs.

Quantitative Easing is a blanket term for an expansive policy that is used to counteract a stagnant market.

Under QE, a bank can use any number of tactics — but the main ones are the ones mentioned above, reducing interest rates and buying huge debt assets (mostly Treasury securities).

The main risk of QE is that with more cash flying around, it becomes worth less, causing people to charge more and thus inflation.

Should you be worried about inflation?

Don’t be worried.

There may be some supply shortages, and prices will go up for some goods.

But three things will keep prices down.

- Reduced demand. People will not have work, and won’t be able to buy as much. This will reduce prices… but not to the point of deflation because of:

- Stimulus from the government. The government will use QE measures to make sure there’s more money around to spend on things — but they’ll be using this to combat deflation.

In short, the world has been through worse crises. Every time, we learn something new, and we always bounce back.